When Do Automated Strategy Fallbacks Take Effect, and What Do They Mean for Stable Operation?

A task is running and results are still coming back.

But something feels off.

Latency becomes uneven.

Retries happen more often.

A few nodes start producing slower responses.

Your throughput looks fine on paper, yet completion time stretches and the output rhythm becomes choppy.

In many systems, that is the exact moment automated strategy fallbacks begin to activate.

Mini conclusion upfront:

Fallbacks kick in when the system detects risk, not only when it detects failure.

Fallbacks protect continuity but often trade speed for stability.

If you do not observe fallback triggers, you will misdiagnose “random performance drift” as external issues.

This article answers one practical question:

when automated fallbacks take effect, what signals usually trigger them, and what they imply for stable long-running operation.

1. What “Strategy Fallback” Actually Means

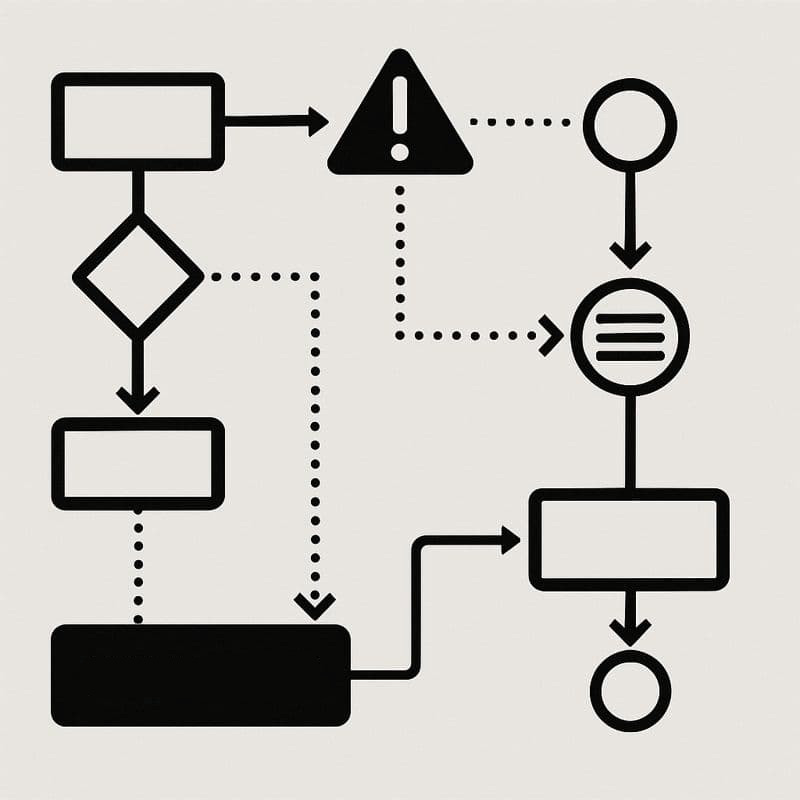

1.1 It Is Not a Single Switch

Fallback is not one mode change.

It is usually a set of gradual behaviors that become more conservative as conditions worsen.

Common fallback behaviors include:

reducing concurrency automatically

routing traffic away from certain nodes

slowing request pacing

increasing delays between retries

preferring safer, more consistent routes

disabling optional steps to keep the core flow alive

The key point is that the system is still running.

It is simply protecting itself.

1.2 Why Teams Often Miss It

Fallbacks are often silent by design.

They do not throw errors.

They do not crash pipelines.

They just reshape the execution rhythm.

So operators see:

work is still completing

no alarms fired

yet performance is worse

That is why fallbacks are frequently mistaken for “network got worse” or “the target got slow.”

2. The Signals That Typically Trigger Fallbacks

2.1 Timing Variance Rising Above a Threshold

Many engines monitor variance more than averages.

Trigger examples:

tail latency grows

jitter becomes less predictable

parallel requests stop finishing together

stage timing drifts from baseline

Even if success remains high, higher variance is treated as early risk.

2.2 Retry Density Becoming Unsafe

A single retry is normal.

A dense retry pattern is a warning.

Trigger examples:

retries cluster in bursts

retry spacing becomes too tight

the same stage retries repeatedly

multiple workers retry in sync

When retry density rises, fallback logic may slow pacing to prevent cascading failure.

2.3 Node Health Degradation

Node pools rarely degrade uniformly.

Trigger examples:

one region starts producing slower handshakes

one node’s success rate slips

a subset of routes shows growing tail behavior

Fallback logic often demotes weak nodes and routes work toward the stable subset.

2.4 Sequencing Integrity Risk

Long tasks often depend on correct order.

Trigger examples:

out of order completions increase

missing segments appear

partial outputs rise

downstream dependencies stall waiting for upstream pieces

When sequencing integrity is threatened, systems often slow down to preserve correctness.

3. What Fallbacks Mean for Stable Operation

3.1 Fallbacks Protect Continuity

Without fallbacks, small instability can spiral into collapse:

retry storms fill queues

weak nodes poison batches

ordering breaks corrupt output

Fallback logic reduces the chance of runaway failure by shifting to safer behavior early.

3.2 Fallbacks Usually Trade Speed for Predictability

Common tradeoffs:

lower peak throughput

higher average completion time

less aggressive parallelism

more conservative node selection

This can be frustrating, but it is often the right decision during long runs because stable progress beats fast failure.

3.3 Fallbacks Can Mask Real Problems

Fallbacks keep work moving, but they can also hide root causes.

Example:

a node is failing

fallback routes around it

output continues

nobody notices until the stable nodes become overloaded

So stable operation requires visibility into when fallback happened and why.

4. When Fallbacks Backfire

Fallbacks are not always good. They backfire when they are too aggressive or poorly tuned.

4.1 Overreacting to Short Bursts

If the system triggers fallback based on very short spikes, it can oscillate:

enter fallback too often

exit too quickly

re enter again

Oscillation creates instability of its own.

4.2 Collapsing Concurrency Too Hard

Dropping concurrency aggressively can:

inflate queue time

extend task duration

increase cost

reduce responsiveness

The system stays stable but becomes inefficient.

4.3 Switching Routes Too Frequently

Frequent switching can destroy consistency:

timing patterns change constantly

success rates become harder to predict

downstream sequencing suffers

A good fallback strategy changes routes carefully, not chaotically.

5. A Practical Fallback Design New Users Can Copy

Step 1: define clear trigger thresholds

use variance and tail latency, not only averages

Step 2: apply gradual fallback stages

stage 1 reduce retry density

stage 2 demote unhealthy nodes

stage 3 reduce concurrency

stage 4 switch to safest routes only

Step 3: add cooldown windows

do not switch modes instantly

avoid oscillation

Step 4: record every fallback event

store what triggered it, what actions were taken, and how long it lasted

Step 5: separate stability from efficiency goals

during fallback, aim to preserve correctness and continuity first

This approach makes fallbacks predictable and easier to tune.

6. Where CloudBypass API Fits Naturally

CloudBypass API helps teams understand fallbacks by making the trigger signals visible.

It can reveal:

phase by phase timing drift

node level health deterioration

retry clustering patterns

route variance across regions

early warning signals before failure spikes

With that visibility, teams can:

tune thresholds based on evidence

avoid overreacting to harmless bursts

identify which nodes cause repeated fallback entry

protect long running stability while keeping efficiency high

Instead of asking “why did the system slow down,” teams can answer “which signal triggered fallback and what changed.”

Automated strategy fallbacks activate when a system detects rising risk in timing, retries, node health, or sequencing integrity.

They protect continuity by becoming more conservative, often trading speed for predictability.

The biggest operational mistake is treating fallback behavior as random performance drift.

Once you measure fallback triggers and record each event, stability becomes controllable and efficiency becomes tunable.